Where to begin?

Often students find writing a proposal quite overwhelming. This is not surprising. Because research is about taking a very complex world and trying to simplify us. It is necessarily filled with chaos doubt and confusion. If that’s what you’re feeling just be reassured that this is a normal part of the process. You’re at the beginning of the process. As you work through your research project you will become more familiar with the literature. You will become more familiar with the research methodologies. So, You’ll gain confidence as you move through it. But at the beginning of the course, it’s much more difficult. Because you’re starting to learn this whole process.

Developing a proposal is the first step in this process of simplifying the complexity to make sense of it.

The research proposal is never really perfect. Because it’s an idea of how you want this research to take place. How it plays out might be very different in the end. But it’s something that you can do. The proposal helps you think through what you think you’re going to do. Then you can adjust it along the way if necessary.

The proposal is a very new and necessary step and I think every student should do a research proposal. Because it helps you to think through all the nuances of your research project before you begin. Rather than having to change in the middle of things you can think them through at the beginning.

Proposal Genres:

Before we begin and get into what goes into a proposal I want to just talk about disciplinary differences. While there are common elements to most research or thesis proposals, there is also a difference. Those differences will be based on disciplines or sub-disciplines. Depending on your discipline you might include different sections. You might collapse some of the sections that I’m going to discuss. You might have additional things that you need to put into the proposal.

Although I’m gonna give you the generic kind of research proposal.

You will need to go and do research in your departments, a faculty, look at examples and see how proposals in your particular are structured. What proposal readers are looking for. But what I’ll give you are the basics. So, just give you an example of what I’m thinking of here is, engineering. So, in engineering, the literature review wouldn’t necessarily be a separate section. What you would find is that the literature review would be either under the introduction or in the method section. The method section would be a very important part of the proposal.

The other difference that I wanted to mention is that Ph.D. level proposals are quite substantially different from masters level proposals. Not only in scope and depth. But also Ph.D. level proposals require much more originality and are more theoretically based more often than not.

The purpose of the proposal:

What is the overall purpose of the proposal? For your proposal Assessor the person who’s going to read us. They want to see that you understand the research process. That you understand the content area that you’re working in. And that you can do this research. For you the proposals provide a map, It’s a guide for you. As you move forward you can look back on your proposal and say what did I want to do here? Okay, yes, I see, that’s what I want to do. Yes, I’m continuing in the direction or no things have changed I need to alter my proposal. It provides you with a pretty good way forward.

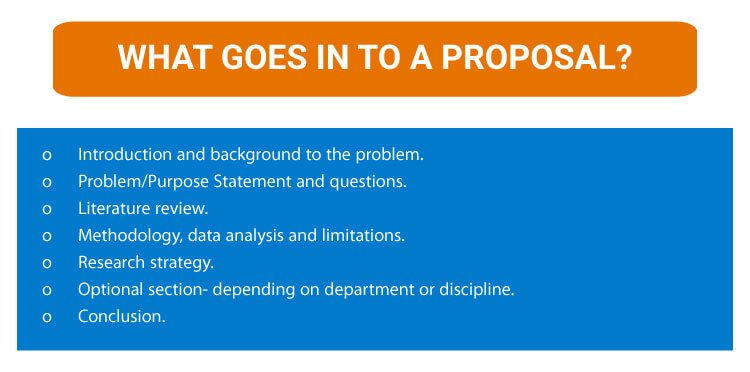

What goes into a proposal?

These are the generic things that go into a proposal. These would be the section that makes up the proposal. You would generally have an introduction and background to the problem. You would have some kind of problem purpose statement and questions. A literature review, methodology, data analysis limitations. So, things around the methodology or the methods, some kind of research strategy, and then there could be a range of other optional sections and these would be a paragraph each depending on what it is? Then a concluding paragraph. I’ll go through each of these in turn and explain them a bit more and this is really for research types of proposals. So, if you’re doing the kind of proposal like in philosophy, you wouldn’t exactly follow the particular format. Because you probably wouldn’t have an empirical research methodology section. Your focus would then be on the literature review.

Take a look at components of Research Proposal

Introduction and background to the problem:

The introductory paragraph is very important. Because this is where you orient your reader to your project. This is where you gradually warm your reader app to the ideas that you’re presenting. In a way, it’s a little bit of a summary of what’s going to come next. But you’re sketching the background for your readers. What your readers asking is, where does this research take place? when? What is the research about? The most important question is why should I read any further? So, really what you want to do is, interest your reader right up in the first paragraph.

The other thing that introductions do, explain to your reader what’s coming next in the proposal. You can sketch it out in a couple of sentences. How this proposal will look like? That the reader knows what’s coming next.

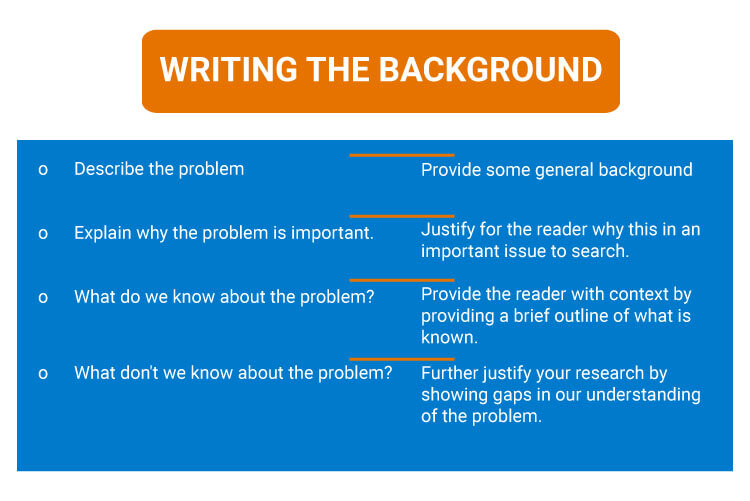

Writing the Background | How is a research proposal written?

The background to the problem is the build app you’re convincing your reader through these multiple layers of arguments. Why this problem is so important? Here you provide some general background on the problem. you’re explaining why this problem is important? Explaining what we know about the problem and that could be in real-world terms. But it also hints at the literature as well. You’re justifying what we don’t know about the problem and again that could be in real-world terms. Or, it could be based on the literature. Setting up the problem in the background.

Background/Foreground | How is a research proposal written?

One of the things that’s quite important when you start conceptualizing your research. So, what you’re doing in developing this proposal is making a whole range of decisions. Around what you will do and what you won’t do. How you’re going to go about doing it and why? Making these decisions that sometimes get quite overwhelming. Trying to move from a topic to a research problem.

One of the ways to think about this is to think about what is going to go into the background and what is going to stay in the foreground. For example, if you take a concept like poverty. Poverty is a very important issue. But it may be in the background of a study that has to do with a poor community, developing income-generating mechanisms. Although poverty is a major problem. The smaller problem that you’re going to focus on is how this community or why this community needs to develop income-generating programs.

Problems are always interlinked and very complicated in the ways that they are interlinked. Deciding what is on center stage in your study and what will move into the background will help you to decide what you’re going to focus on and what you’re not going to focus on. This is setting up the scope and the limitation of the study.

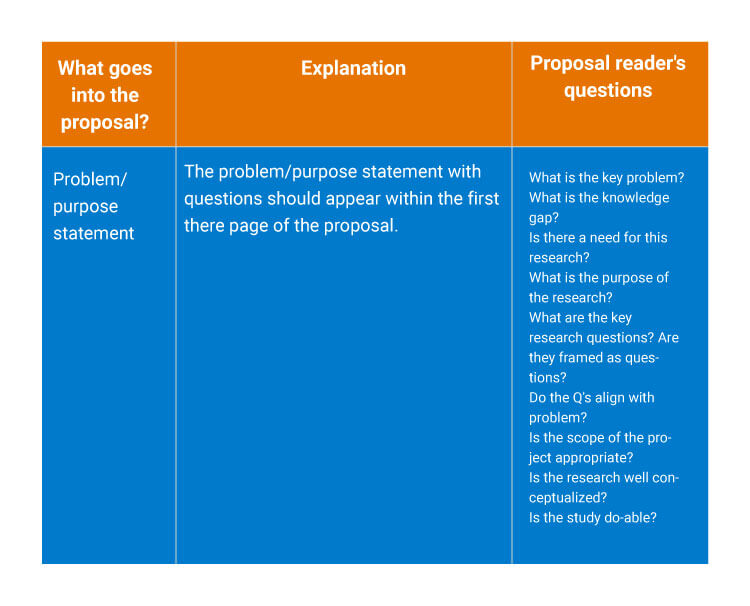

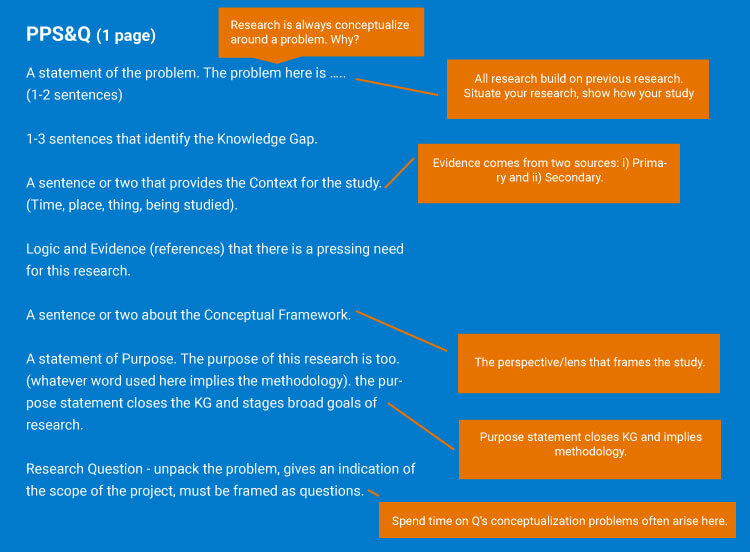

Problem, Purpose statement & Questions:

This part of the proposal is the problem purpose statement. You know many people who teach workshops on this. Or, You have many videos on this, May not set up the problem purpose statement in the same way as I have done here. This is my argument for the need for this kind of problem purpose statement. Which I have found very very useful in workshops. The way I’m setting up the problem purpose statement here is set up in a particular way and it’s not always set up like this. But, it’s a way that works as far as I’m concerned.

What the problem purpose statement is, It’s a very succinct short statement.

No longer than a page about your research project. It’s the core conceptualization of the research project. It should appear within the first three pages of the proposal. If you get a question about what is this research about, your reader is looking for their problem purpose statements. The proposal reader’s questions will be answered by this. What is the key problem? What is the knowledge gap? Is there a need for this research? What is the purpose of the research? What are the key research questions? Are they framed as questions? Do the questions align with the problem? Is the scope of the project appropriate? Is the research well conceptualized and is the study doable?

There are one or two sentences on a statement of the problem and it’s quite hard to articulate the problem often. Using the sentence the problem here is and finishing that can sometimes help. One or two to three sentences on identifying the knowledge gap in the literature. A sentence or two that provides the context of the study. Where is this taking place? What is the study about? A sentence or two about the conceptual framework or the research.

This is only relevant if you’re doing doctoral research or if it’s in relevance in your particular file.

The logic and evidence refer to the order that these four things are presented in and that order will depend on your topic and your disciplinary kind of context. For example, if your topic is very contextually heavy or contextually bound. Then you might begin with the context. If your topic is based on a knowledge gap, then you might begin with the knowledge gap.

If your problem is a big real-world problem then you might want to begin with the problem. So, how you order all of this will depend on the logic of your research. The evidence refers to the fact that you need to provide sources. If you can, for the existence of the problem. Convincing your reader that this problem is important will be substantially stronger if you have sources to back that up. And the same thing with the knowledge gap and the other parts of the problem statements.

What follows a problem statement is the purpose statement and this really should have a sentence.

The purpose of this research is to. Often people think that they shouldn’t put that sentence in and when they don’t the very first question they get is, what is the purpose of this research? It’s very easy to put that sentence in and it will be clearly stated. Whatever you used to finish that sentence implies your methodology. You could add a sentence or two that expands on the methodology after the purpose statements. The purpose statement should close the knowledge gap that you identify earlier.

It should state the broad goals of the research. This is then followed by the research questions. And the research questions should unpack the problem you’ve identified. So, you have to go back to those sentences where you identify the problem and draw your questions out of that. The questions will give you the scope of the project and they should be framed as questions.

If you develop a hypothesis, you would do it after this. The research question allows you to focus on the project. Developing the hypothesis after that is a little bit easier than trying to do it before you’ve developed your questions.

Literature Review | How is a research proposal written?

The literature review is often one of the most difficult parts of the research proposal. Because you may not know the literature well. At this point and again what I would say to you is, just trust that you will get to know the literature much more as you go through this process. That you have to start somewhere.

What the literature review does is, that it situate your research within the border research literature. The studies that have been conducted on your topic or problem. What you do with it here is you tell your reader this is what’s been done in this area and this is where my research fits. That fits up a rationale for the study because you’re identifying a gap in a knowledge gap. And it sets up an academic rationale for the study. You’re also evaluating the literature concerning your particular project. Not just describing it. You’re evaluating it and you’re saying although this study was conducted here this was missing from it. My study is going to fill that gap. That’s an evaluation.

You want to be showing that you have read some text very deeply.

And that you have a broad enough overview of the literature. This is very tricky because, in the proposal, the literature review section is not very long. It’s quite a difficult balance. But the more you read the more confident you’ll be about your project, the more you’ll know about it and it will show in the proposal. But of course, you don’t want to be spending years and years working on the literature review of your proposal. You do need to balance things art.

The other thing you would do in the proposal is to explain the conceptual framework. Your proposal reader’s question would be has the student read enough to inform the study. Is the study situated in the literature? Does the student have a good understanding of up to date? Very important key thinkers issues debate relevant to the study. Has the student been able to describe, analyze and critically evaluate what he or she has read? Is the literature review related to the study at hand? So, is its relevance, and particularly for doctoral study students is the conceptual framework and you know unpacked in the literature review.

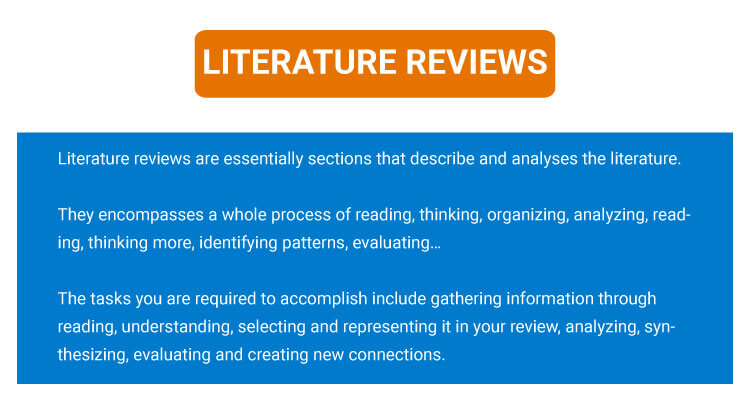

literature reviews essentially describe and analyze the literature.

You need both the description and the analysis. The description would be something like this particular study that was conducted in this place or area. That the methodology they used was x, y & z. The results they came up with wan A, B & C. That’s a description just telling you what summarizing in a sense what’s happened in that study.

The analysis would be looking at the individual paper and trying to analyze the consistency of that research project. Or it could also be looking at several different papers or articles or book chapters or books and identifying patterns across those texts. Analyzing, involves, comparing, contrasting, grouping, looking for similarities, looking for differences.

In the literature review, you want to both describe the literature you reading as well as analyze it. Even grouping things into themes would be a level of analysis. Really what you readers are looking to see is that you can move from lower-order thinking skills. Which is understanding and summarizing readings to higher-order thinking skills? Which is then analyzing, synthesizing, and evaluating that literature. Literature reviews must contain analysis as well as the description.

The literature review does for you | How is a research proposal written?

What is the literature review do for you? It helps you to situate, such a read your study within the literature by identifying the knowledge gap. Helps you to set up the theoretical framework. It could even help you set up the criteria for data analysis. You could have a section in the literature review where you unpack how you’re going to analyze this date If it’s relevant. If you are using a particular theorist and what I’m thinking about now is perhaps. If we go and discourse analysis, then you could say to app the theoretical framework in the literature review as well as the data analysis, and then later when you analyze your data your reader will already know what you intend to do.

The literature review also helps you to explain your use of concepts.

We’re not talking about dictionary definitions here. We’re talking about the different meanings within the literature and how people have used concepts. Academic work is always contested. People have different perspectives. There’s very often, not a lot of consensus. Well, there may be consensus but there will always be people who argue against a particular issue. That’s why you cant’s use dictionary definitions. Because they will be contested meaning around concepts in the literature. This is what you want to show. You want to show the different meanings and then you want to align yourself with one of those meanings. And explain why you’re aligning yourself that way.

You might also in the literature review set up a perspective that informs your methodology.

If it’s important if you are taking a narrative approach, then you know perhaps setting up a postmodern narrative analysis in the literature review becomes important to you. You’re also developing an argument which I’ll come back to about why you have selected these bodies of literature and how they relate to your study?

The other thing that’s very important in a literature review is the counter-arguments. This is because scholarly works try to prevent or try to avoid looking like you are biased or subjective. Scholarly work tends to want some kind of balance. If you are presenting only your argument your perspective. Then it’s very one-sided. Really what readers like to see is that you have read the counter-arguments. That you have taken note of the counter-arguments. Provided a rebuttal in some way to them. Showing counter-arguments is very important in a literature review.

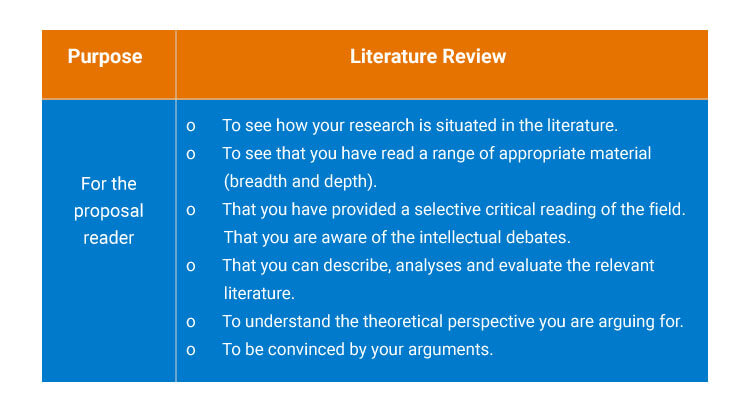

For the proposal reader | How is a research proposal written?

For the proposal reader, the want to know that you can situate this research in literature. That you’ve been able to read a range of appropriate material and that it’s relevant. That you’ve been able to select from that field and read critically. That you’re aware of the intellectual debates. That you can move from lower-order thinking to higher-order thinking. That you understand that theoretical perspective. And they want to be convinced by the arguments you’re making in the literature review.

Reading and Note-Taking | How is a research proposal written?

Literature reviews involve systematic reading. Setting up some kind of method is helpful to you and helpful to your reader. That your readers have confidence that you haven’t chaotically gone about this. That you have had some kind of system. Your system could be to start with, for example, a couple of key articles that you read in-depth and then trace the sources in those articles and then read more articles in-depth and trace the sources in those articles. That’s starting small and growing bigger.

Another method could be doing searches through library databases and on Google for using keywords.

Tracking your keywords and just collecting PDFs and documents, books to do with the topic. To do with the research problem and then once you’ve collected than organize them into some kind of system. And then perhaps read all the abstracts and then finally focus articles to read articles in depth. What you’re doing there is much more of a global search and then narrowing down.

Those are the two kinds of ways of reading. The first one is from the narrow to the general and the specific to the general. The other one is from the general to specific. University libraries generally have the most wonderful librarian. So, get help from librarians. If you can they know their stuff and they can help you enormously. Be very organized in your note-taking, because this is a long-term project.

You might be taking notes in your one and then using them again in year four and by their time you’ve forgotten which part of your note was from the text and which part was your thoughts. If you take something from a text, verbatim you’ll put that in quotation marks with the page number. If you write your notes underneath that. You’ll highlight them or put them in a different font. So, that is very clear, what comes from the text and what were your thoughts at the time. That you don’t inadvertently plagiarize down the road.

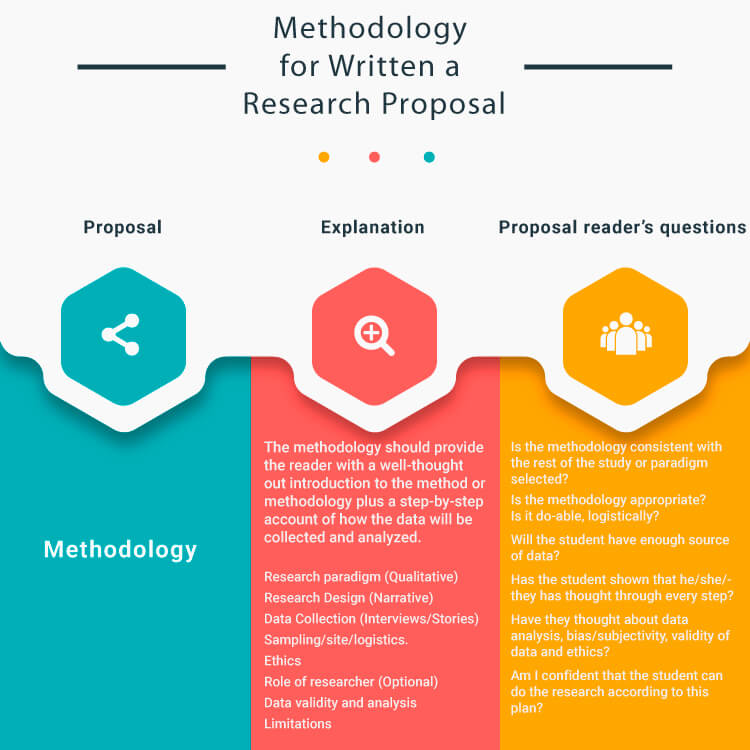

Methodology | How is a research proposal written?

This is a very important part of a research proposal. This is the crux of the matter actually for your readers. This section will be written differently depending on your discipline. I’ve called it methodology. But in some disciplines, this would be called research methods.

The methodology incorporates the philosophy behind the method. In some disciplines, this is not as important. But in qualitative research, this is much more relevant. The section that I’ve got down here would be paragraphs within the methodology section of a proposal. You would explain the research paradigm. Where you would explain why this paradigm is relevant for this particular topic. You would then look at the research design.

Which should link to the research paradigm.

Which there should be a logic to it and you need to explain why this design provides an overarching model or method for your data collection method. Then in the data collection, you went there is the step-by-step process of how you will collect the data. What will you do first? What will you do next after this? You will also include a section on your population, your sampling method, the research sites anything else that you need to include about the research. So, that your reader can see that you’ve thought of all the steps along the way.

You might include an ethic section. Not all proposals do that. It’s not always relevant.

But you might include an ethics section if it is relevant for qualitative research. Sometimes having a section on the role of the researchers is important. That’s because you’re trying to address the issue of subjectivity or bias. You will generally want to have some kind of section on how this method will deliver valid data. You would also perhaps have a section on how you include analyzing the data. I think it’s very useful to include data analysis in the proposal. Because you get feedback on that and later on when you come to analyze the day. So, you already have this all set up.

Some methodologies the analysis is set up anyway, so that won’t be relative. But in a lot of there won’t be relevant. But, in a lot of qualitative research, the analysis is not set up ahead of time. And it is very useful to do that.

In the last section, you might want to include other limitations. If for a logistical reason, your sample is fairly small then you want to note that. Because really what you’re telling your reader, is I understand I have thought through and know what the problems are with this. But, I still think that it will be a valid research project.

What your reader looking to see is whether you’ve thought through all the steps.

Whether, there’s a consistency in the research paradigm design and data collection. All of that is related in a consistent way to your research problem. Whether you’ll be able to answer the research questions through the data that you’ve collected. Will you have enough sources of data for the size of your project? If you’re doing a doctoral study, will you have enough to complete the doctoral study? Have you thought about the kind of ethical issues, subjectivity issues, validity issues? The reader wants to be confident you can go out and undertake this research tomorrow if necessary.

Research Strategy | How is a research proposal written?

The next section in a research proposal is the research strategy. This is again not one that is included in all research proposals. But, I think it’s very useful for project planning. I would suggest that you should do it anyway even if you don’t include us in the proposal. This is where you set up the timeline for the research.

Provide a detailed plan of when you intend to do all the steps. People use Gannt charts because you can block out months in those charts. But, it gives you a schedule and it’s really useful for keeping to the deadlines that you say to yourself. And helping you manage what is a big project.

Optional section | How is a research proposal written?

It could be several optional sections that go into the proposal and this is really up to you. Your supervisor and your departmental discipline. I would suggest that you go and ask people to look at the example of proposals. In your discipline, if you can and ask your, supervisor, what other sections could be included. You know, quite a few people like to have a section that says the significance of the research. Others might be asked to present the impact of the research. In education, for example, you might be asked to provide implications for practices. But, really what your reader wants to know is whether you have provided enough to show that you can go and do this research.

Other things you could include perhaps as appendices would be your interview, in-depth interview questions. If you have prepared a survey, you could attach the instruments. You might want to describe your population. Those kinds of details can provide additional information to show that you have thought this through. You could also order the section differently the order of the section is not quite as important as that they are in there.

Conclusion | How is a research proposal written?

Then finally we come to the conclusion. Although you provide a summary in the conclusion you want to use your conclusion to emphasize key points. You want to emphasize the need for the study more than anything else. That you can convince your reader.

References | How is a research proposal written?

Then, of course, you want to have your references. In whatever format is required of you. And what your reader will be looking for, is to see do you have up-to-date sources. Are your sources all from 10 years ago and of course there might be relevant in your topic. But they’re going to look for relevant sources to this particular topic.

The argument in a proposal | How is a research proposal written?

I just wanted to add a slide on arguments in a proposal. Because I’ve given you the sections that generally go into the proposal. But, in those sections, you are making these arguments. And what I would ask people to do in my workshops would be to take index cards, and to write out all these arguments in one sentence. Then to go back to your proposal and see whether those arguments have been pulled through the proposal. Whether you’ve provided evidence for them.

One of the key arguments you’re making is that there’s an urgent need for this research. That the research problem is relevant and important. That could be related to time, that it’s relevant and important now, or something that happened in the past. That makes it relevant and important now.

Sub arguments within the proposal are the knowledge gap. You’re making an argument that there is a knowledge gap and that it needs to be filled. This methodology is the most appropriate, most relevant, and not another one, and that this conceptual framework is the most fitting lens to view this project. Those are some of the arguments that you need to think through in your proposal.

How long? | How is a research proposal written?

The question I always get in workshops is how long should the proposal be. Your particular department or faculty will have a guideline for how long the proposal should be. You need to look that up. What’s more important here is the weighting. The weighting of the proposal lies in the literature review and the methodology. Generally, proposals are quite short documents. They’re about 15 pages maybe 20 when compared to the overall thesis.

The bulk of the focus should be on the literature review which is setting up the need for the project and the methodology which is outlining how you will go about collecting the data. Then the other sections fall in the pages on either side of it. Make sure when you’ve written your proposal that you don’t have an overly long introduction and a short methodology. You want to make sure that you’ve got the weighting right.

The Title | How is a research proposal written?

A quick word on the title, the title is very important. Because that’s what people see first and often people say to have their titles before they do their proposal and then sometimes the proposal shifts and the title doesn’t match. You want to make sure the title matches. In some disciplines, it’s important to encapsulate the whole topic in the title. Other disciplines allow for more creativity, more generally focused topics. But really what I would suggest to you is if someone going to do a keyword search, how would they find your thesis. What would the keywords need to be? Those keywords need to be in your title. Think about it like that.

Thank you for reading.