A supply chain can be viewed as a system of processes that cut across organizations and deliver customer value. Rather than as a series of separate organizations and functions. In this case, the focus is not just to manage each process within the organization. But to manage processes across the entire supply chain.

One example might be the order management process, which includes managing the customer order from placement to product receipt through the entire chain. This requires process thinking and requires managers to view the collection of processes as a system designed to satisfy customer needs.

Let’s consider the situation of ASICS, from below. Their distribution process required managing the entire network as a system. Their only distribution center—which was the hub of the network—had a maximum capacity of 50,000 units per day. When the rest of the network began processing 70,000 units per day, the distribution center could not accommodate this volume.

The result was a “bottleneck,” or constraint, in the network that limited how much the system could process. It was not enough to grow sales and improve each individual facility in the supply chain. The supply chain network needed to be improved as a system.

Situation of ASICS

In 1949, Mr. Kihachiro Onitsuka began making basketball shoes out of his living room in Kobe, Japan. He chose to make sports shoes, as he thought this to be the best way to encourage the young to play sports. He wanted his shoes to be the best in footwear and chose to call his company ASICS, an acronym for the Latin phrase anima sana in corpore sano, meaning “a sound mind in a sound body.”

After years of hard work ASICS had become a leading maker of athletic footwear, sports apparel, and accessories. Today ASICS’ worldwide sales total around $2.4 billion. Although its great success was welcome, ASICS found it to be both a blessing and a curse.

In 2008 ASICS America found itself growing 21% annually, and the company found it difficult to keep ahead of demand. ASICS had only one distribution center in the United States, which had reached capacity. This single distribution center (DC), located in Southaven, Mississippi, was able to handle a maximum of 50,000 units per day. However, the growth in demand resulted in 70,000 units per day being shipped to the DC.

This capacity constraint was not only slowing down order fulfillment, but also was now preventing the company from serving new customers and markets. The DC had become a “bottleneck” in the supply chain design network causing service slowdowns. The company understood that the supply chain network had to be changed if they were going to support this new level of demand.

The company’s U.S. network was fairly straightforward. It used contract manufacturers in China, Vietnam, and Indonesia to make its shoes and clothing. Those items were shipped in ocean containers to the ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach. It then used a third-party logistics provider—APL Logistics (APLL)—to unload ASICS’ ocean containers. The merchandise was then reloaded onto 53-foot trailers for shipment to the 350,000-square-foot DC in Southaven. That facility then shipped orders to the company’s 3,000 retail customers in the United States.

ASICS understood that this current network had to be restructured. It turned to Fortna Inc., a consulting company, for help. After analyzing the network and current demands, Fortna recommended shifting some distribution operations to the West Coast to provide relief for the current distribution center and then constructing a second distribution center close to the original site. Fortna’s analysis indicated that establishing a West Coast operation to break down imported containers and build mixed loads for shipment to customers in the western United States could save the company time and money.

The company immediately began to divert a portion of its orders directly to customers and bypass its current distribution center, using its third-party logistics (3PL) provider.

These were typically full container loads of products already destined for customers on the West Coast. Its problems had been solved. In 2011 the company constructed a second distribution center in Byhalia, Mississippi, about 20 miles from the current distribution center. The new 520,000-square-foot facility uses state-of-the-art technology. The company completely transformed the way it processes orders. It uses technology to efficiently manage all assets and shipping operations, such as using mobile equipment to keep real-time checks of inventory. The company has positioned itself for continued growth and has learned that a good distribution network requires more than buildings and facilities. Mr. Onitsuka would be proud.

Adapted from: Napolitano, Maida. “ASICS Finds the Perfect Fit.” Logistics Management, February, 2013.

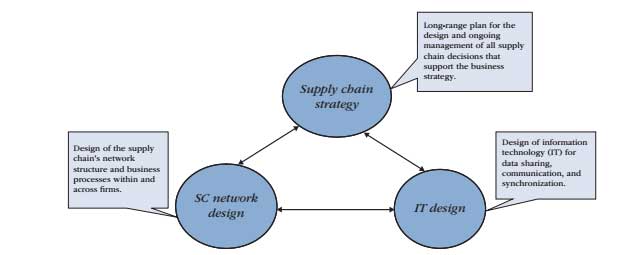

Two key elements support this strategy. The first is the supply chain network design, which includes the physical structure and business processes included in the system. The second is the information technology (IT) design, which enables data sharing, communication, and process synchronization.

IT is the backbone of supply chain management (SCM) that enables managing processes. Without IT, communication, coordination, and decision making across the supply chain could not take place. Together the supply chain network design and IT system design support the supply chain strategy, as shown in Figure 1.1. These elements have to be aligned and work in unison as one system.

What Is a Business Process?

Given that supply chains can be viewed as a collection of processes, we need to see what makes a process. A business process is a structured set of activities or steps with specified outcomes. Consider the “process” involved in enrolling in a class at your university. There are application forms to be reviewed by the admissions office. Financial firms to complete at the bursar’s office, and class registration to be completed at the registrar’s office.

The sequence of steps required, their timing and coordination. The simplicity of forms and their ease of submission are all part of the enrollment “process.” The sequence of process steps goes beyond the organization and cuts across a supply chain network, as in the case of ASICS. ASICS’ distribution process required unloading shipments from Asia at California ports. Loading them onto trailers for shipments to the distribution center in Mississippi, and then sending shipments to individual retail customers.

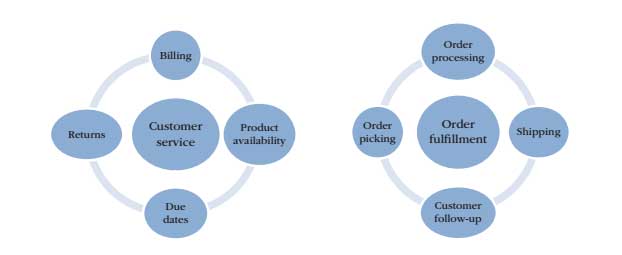

Organizations, and entire supply chains, can be viewed as a collection of processes. Rather than just a collection of departments or functions. 1 For example, there is the customer service process that involves a series of activities designed to enhance the level of customer satisfaction by meeting or exceeding their expectations. This may involve a series of well-coordinated activities. Such as billing and invoicing, handling product returns, providing real-time information on promised shipping dates, and product availability.

Another example is the order fulfillment process, which involves ensuring that customer orders are filled. It may involve activities such as receiving and processing the order, ensuring movement of product and delivery, and customer follow-up. Other examples of processes include the manufacturing process, which involves ensuring the production of products; the demand management process, which balances demand requirements with operational and supply chain capabilities; and the distribution process, which involves distributing and delivering products to specified locations.

Organizations have many other processes, with each having a series of activities designed to create a particular output for the customer. Whether it be a service or a tangible product. The output is a result of the process that produces it. If we want to improve the output, we must improve the process. Process improvement involves making changes and enhancements to the process. In the example of course registration, this may involve reducing the time it takes to register for a class by reducing the number of forms needed. Simplifying each form, or shortening the time it takes to review them.

Every process has structural and resource constraints that limit its amount of output. Because processes are a series of activities, the constraints of each activity are important as well as how the activities are linked. For example, if the university’s bursar’s office is slow in processing payments. There may be a delay in course registration as the registrar’s office waits to get financial approval. In the example of ASICS, the slow processing at the distribution center prevented goods from moving through the system.

Notice that processes involve many organizational functions as shown in Figure 1.2. For example, the customer service process cuts across a number of different functions. It must involve marketing that interfaces with the customer, logistics that ensure product delivery and movement, and operations that may deal with repairs. Similarly, order fulfillment requires operations to ensure order availability and processing. Logistics to arrange for order picking and shipping, and marketing for customer follow-up.

For processes to be effective and efficient, organizational functions must work together and be well coordinated. In addition, these processes require coordinating with suppliers and customers. As such, they cut across not only organizational functions but also the entire supply chain.

Managing Supply Chain Processes

Just as organizations need to coordinate internal functions for processes to run efficiently, they must do so across the supply chain. As the entire supply chain is a collection of processes. Rather than separate organizations and functions, the focus is to manage them across the entire supply chain. This requires process thinking and requires managers to view the process as a system designed to satisfy customer needs.

Transactional view

There are two differing views on how to manage processes across the supply chain. The first is the transactional view that focuses on making supply chain processes more efficient and effective based on quantitative metrics. This can be achieved through supply chain network redesign to promote speed and eliminate redundancy. By standardizing transactions to improve efficiency, and by implementing better information technology to improve the transfer of information and improve accuracy.

Relationship view

The second, the relationship view, is focused on managing relationships across the supply chain. This involves managing relationships between people and organizations and linking-up processes across organizations of the supply chain. For example, this might mean managing the order fulfillment process throughout the entire chain coordinating with suppliers and measuring performance along the chain. This also means that managers from each organization who are part of the process coordinate activities, work toward common goals, and have a common language.

Each approach to managing processes across the supply chain has its advantages. With the first, the focus is to make supply chain transactions more efficient and effective based on measurable metrics. The second, objective is to structure interfirm relationships in the supply chain for the long-term benefit of all the supply chain members.

This requires a joint vision and partnering. Ultimately the best way to manage processes across the supply chain is to use both approaches—focus on efficiency of transactions and create long-term interfirm relationships.

Once again consider ASICS. It focused on both approaches. It first brought efficiency to the distribution network by balancing flows through the network. It also relied on its relationship with its 3PL provider to take over some duties and handle the “overflow” of goods.