We will start this post work by examining the inscribed Middle Kingdom of Egypt statue. This object is of interest for two very different reasons. Firstly, it is a beautiful artifact that introduces us to the type of sculpture being purchased by the Middle Kingdom elite.

Secondly, it is the famous “Spinning Statue”: an artifact apparently capable of moving of its own accord. In 2013, this phenomenon led many people to accept that the statue had supernatural powers.

The Middle Kingdom pharaohs built pyramids, but unlike the stone pyramids of the Old Kingdom, many of theirs were mud-brick structures hidden beneath a polished limestone exterior. These pyramids may have been cheaper, and faster to build, than the Old Kingdom pyramids but they still required a dedicated workforce.

The town of Kahun (also known as Lahun, and Illahun) was built to house the workers engaged in building the nearby pyramid of the 12th Dynasty king Senusret II.

When Kahun was eventually abandoned, the townsfolk left behind many domestic items (including tools, toys, religious items, and papyri) which, thanks to the town’s unusual desert location, have survived to allow us a glimpse of daily life. We will be looking at some of these artifacts in this section.

Finally, we will consider two very different collections of Middle Kingdom grave goods: the tomb of the “Two Brothers” (who may, or may not, have been brothers) and the “Ramesseum Tomb Group”, recovered from a Theban shaft tomb.

Historical Overview of the Middle Kingdom of Egypt

Gradually, the independent local governors of the Valley and the Delta started to form alliances until two dominant dynasties emerged; a northern dynasty based at Herakleopolis and a rival southern dynasty based at Thebes.

The Thebans, under the leadership of Mentuhotep II, re-united Egypt and, during the 12th Dynasty, established a new capital city (which is now lost), at the site of Itj-Tawy, somewhere near the Faiyum.

The Middle Kingdom kings followed the pattern set by their Old Kingdom predecessors and built pyramids. However, many of their pyramids had mudbrick cores, cased with fine quality limestone.

Literature and the arts flourished, there were successful military and trading missions beyond Egypt’s borders, and an Egyptian empire developed in northern Nubia.

But these were difficult times in the wider Mediterranean world, and as Egypt grew increasingly prosperous she attracted a steady flow of foreigners who settled in the Delta.

Here they formed sizeable independent communities. This increasing immigration, coinciding with a series of unusually high Nile levels, caused discontent amongst the local governors (or nomarchs). A succession of weak kings heralded the collapse of central authority and the Middle Kingdom faded away.

The Pyramid of Senusret II and the town of Kahun

In this section, I will be looking at the pyramid built by the 12th Dynasty king, Senusret II, and at the associated pyramid builders’ town of Kahun. Senusret II built his pyramid near the opening to the Fayium. The pyramid was made of mud brick and it had an outer casing of fine limestone.

This caused the pyramid to shine in the strong sunlight. Because of this, the Egyptians named the pyramid Senusret Shines. Today, as you can see from this picture, only the mud-brick core is visible. The original stone casing was removed and reused many years ago.

With the stone outer layer removed the mud-brick core has eroded away. Originally the pyramid stood approximately 48 meters or 158 feet high. When complete it would have looked as if it was built entirely from stone. The pyramid was robbed in antiquity, and although a red granite sarcophagus was found in the burial chamber, the king’s mummy was lost.

As it was made of mud brick, the pyramid could be built much faster than the stone pyramids that were built during the Old Kingdom. However, it still needed a team of workers to build it, and these workers had to live somewhere near the building site.

So, the workers and their families were housed in a purpose-built town also built of mud brick, which they called ‘Hetep-Senusret mar Haru’, or content is Senusret the Justified.

When the pyramid was built and the king dead and buried inside it, this village continued to be occupied by a community dedicated to making offerings to the cult of the dead king. This community included scribes, priests, farmers, and their families.

The state provided the pyramid workers with basic terraced housing, while their supervisors and officials were housed in larger complexes, which included not only luxurious housing but offices and granaries. For every large house, there were roughly 20 smaller houses.

The pyramid worker’s village was excavated by British Egyptologist Flinders Petrie intermittently between 1889 and 1920. There’s been little work at the site since. And today it is very difficult to imagine the once-bustling town that existed here.

This photograph was taken looking across the site. Notice a large number of broken pots or potsherds on the surface. In the distance, you can see the pyramids of Senusret II. If you look carefully, you might be able to see the traces of the ancient mud-brick walls beneath the sand.

The town, like many other Egyptian settlements, was surrounded by a mud-brick wall.

It has been suggested that the largest complex within the town may have provided accommodation for the king. This complex is today given the name Acropolis.

This photograph is taken from the top of the Acropolis, looking across the town. Notice the sharp difference between the desert, and the green of the modern fields. You should also be able to see some ancient mud bricks sticking up out of the sand.

Today, this archaeological site is known by the modern name of Kahun. In fact, this name is a mistake. When Flinders Petrie first visited the site, he asked an old man what the nearby village was called. Petrie must have misheard the man, as the name of the nearby village was either Lahun or Ilahun.

Unfortunately, all three names, Kahun, Lahun, and Ilahun are used by Egyptologists today. So, if you want to read up about this site, you’ll have to look for all three names. As we’ve already seen, many of the Kahun houses yielded daily life objects left behind when the town was abandoned.

Kahun has also provided a large collection of Middle Kingdom texts, written on papyrus. These texts deal both with the life of the town and with the running of its temple. One important document is the Kahun Medical Papyrus, a document which deals with gynecological problems.

The most commonly found object is pottery. Here you can see the remains of ancient bread molds littering the surface of the site. As the name suggests, these are molds used when baking bread.

Kahun is a dry and sandy site. Because of this, many organic artifacts have survived. This is unusual. We are accustomed to seeing objects of wood and basketry being discovered in Egyptian tombs, but it is rare to find them outside the tomb.

Here, for example, you can see a beautifully made basket with a lid and a wooden box, which when discovered, held juniper berries. We have no idea what these berries were used for.

This is a very important tool. It is a wooden brick mold. To create a brick, the workmen would fill this mold with a stiff clay and water mixture. Then remove the mold and leave the brick to dry in the hot sun.

Many hundreds of regular-sized bricks could be made this way in one day. There was no need to fire bricks in an oven or kiln.

Here, we have a series of stone tools made from flint or chert. They remind us that although the workmen of the Middle Kingdom used copper and bronze tools, they continued to use stone tools as well. Flint makes an extremely sharp and relatively cheap blade. It can also be used to spark a fire.

Finally, here we have a simple ball. It seems likely that this was a child’s toy. Tomb scenes show girls catching and throwing balls, while boys hit balls with sticks. This artifact reminds us that Kahun was not just a pyramid worker’s village. It was home to many families whose children played, just as children play today.

The Two Brothers (note: contains brief images of human remains)

One of the most famous sets of objects in the Manchester Museum is the tomb group of the so-called Two Brothers, dating to the Middle Kingdom around 1800 BCE.

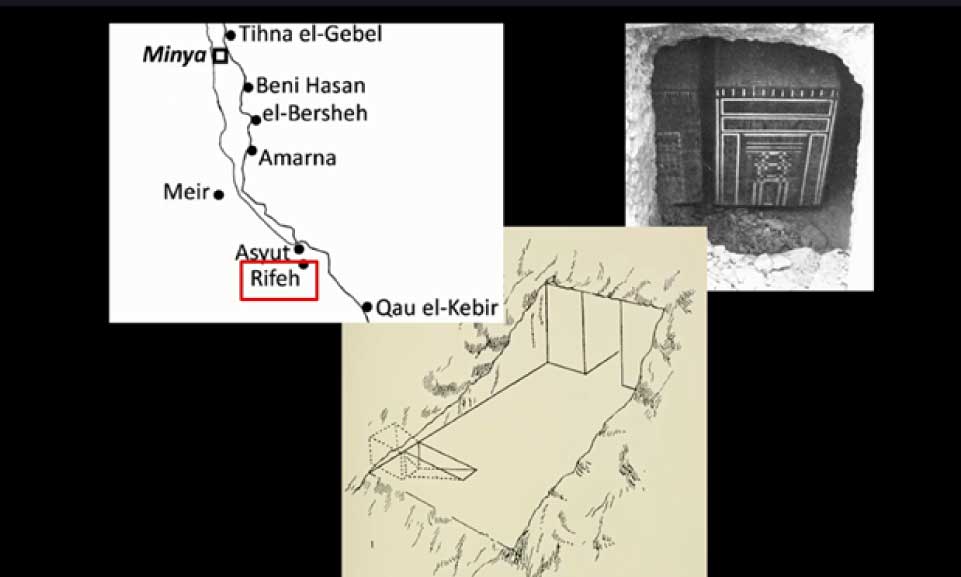

The tomb was found intact in 1907 at the site of Deir Rifeh in Middle Egypt.

It was discovered by an Egyptian workman named Erfai working with a man called Ernest Mackay, a British archaeologist, and assistant to the famous Egyptologist, William Matthew Flinders Petrie.

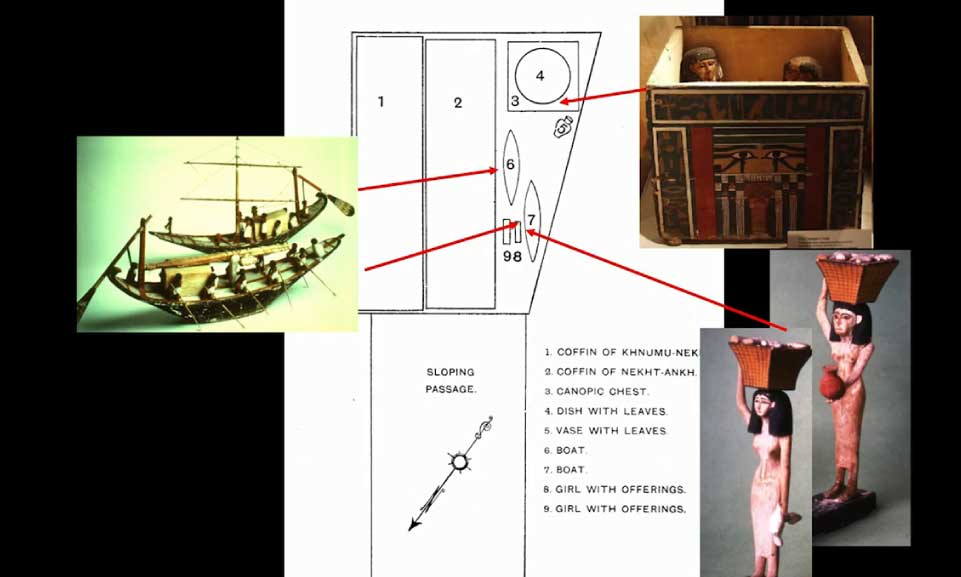

The tomb contained two sets of coffins, a canopic chest, model boats, and statuettes made of wood.

Unusually, rather than the objects being split up and sent to different museums, the entire tomb group was moved to Manchester after local interest quickly raised the necessary funds.

The tomb belonged to two men one named, Nekht-ankh, and the other named Khnum-nakht. Inscriptions on the coffins, name a woman called Khnum-AA as their mother, hence their designation as the ‘Two Brothers’. The tomb contained the mummies of the two men in anthropoid or human-shaped coffins.

These coffins were placed on their sides to enable them to magically see out of the eye panel on the sides of the outer rectangular coffins.

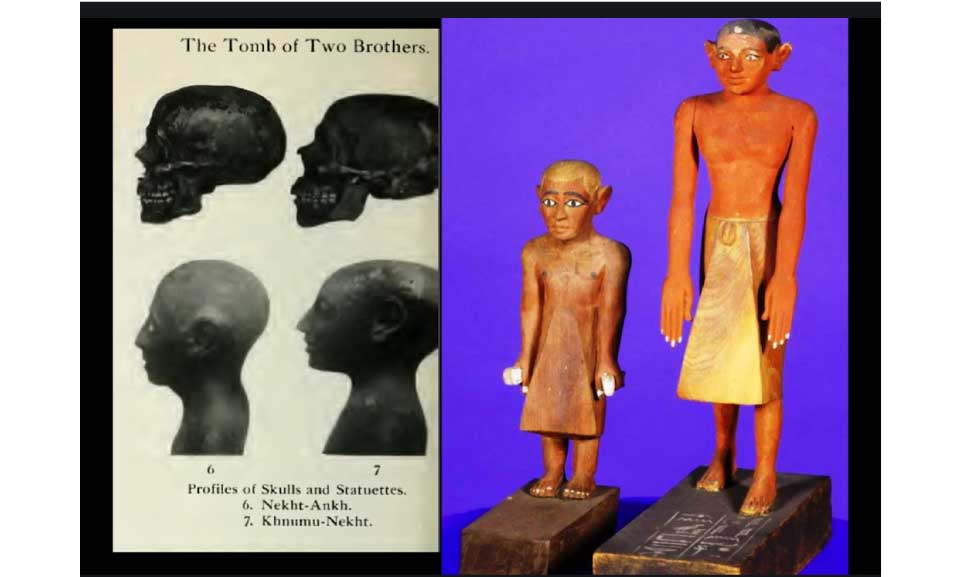

The mummies of the men were unwrapped in 1908 by Margaret Murray in one of the first public and scientific unwrappings in the United Kingdom. Examination of the skeleton showed that Nakht-Ankh had bone development consistent with him being a eunuch and that he had lived to be around 60, which is relatively a ripe old age for ancient Egypt.

Khnum-nakht died younger around 40 and had had severe curvature of the spine. Anatomic variation of the brothers’ skeletons led researchers to doubt that the men were, in fact, brothers. And recent DNA testing has proved inconclusive as to the relationship.

Both men claim to be the sons of local governors, and the rich burial goods indicate that they were wealthy members of society. Inscriptions in the tomb chapels of local governors around this time boast about how generous these officials were, giving food to the hungry, clothes to the naked, and adopting orphans.

Although Egyptologists tend to think of these claims as a series of cliches, adoption documents are known from later in Egyptian history. The ‘Two Brothers’ may, therefore, actually provide a rare archaeological glimpse into the practice of adoption in ancient Egypt.

Ramesseum Tomb Group

The Ramesseum tomb group is one of the most intriguing groups of objects housed in the Manchester Museum Egyptology collection.

It was discovered in 1895 by the British archaeologists William Matthew Flinders Petrie and James Quibell in a shaft tomb of the Middle Kingdom date from around 1700 BCE.

It was under a much later memorial temple of King Ramesses II, the so-called Ramesseum. The objects included a wooden box containing a number of papyrus scrolls, now housed in the British Museum with literary and magical texts on them. Most of the other objects came to the Manchester Museum.

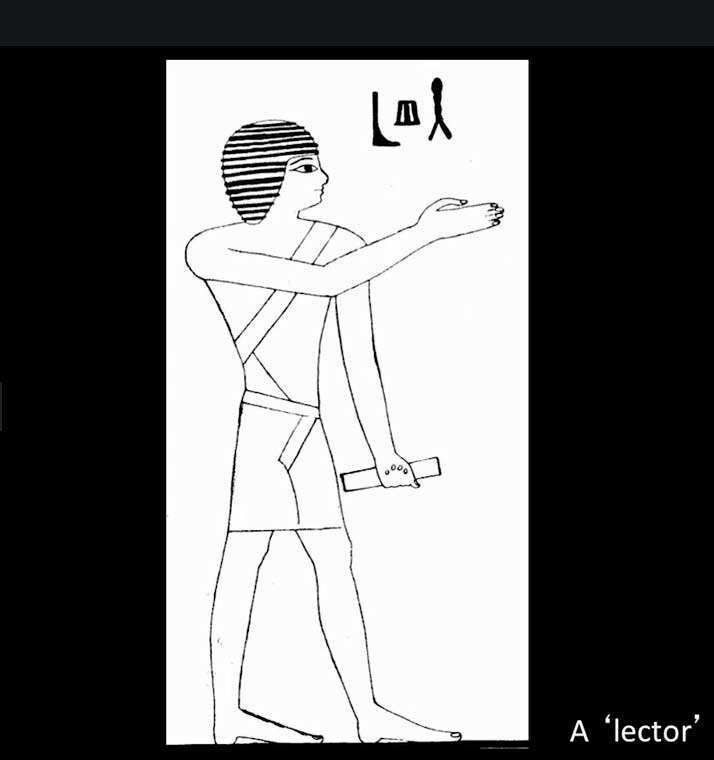

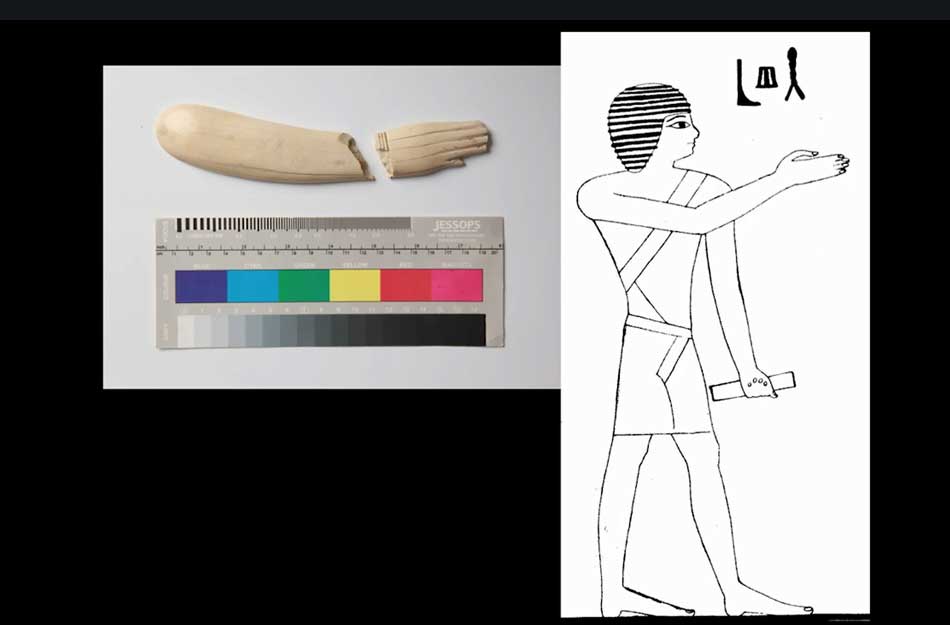

These include a bundle of some 118 short reeds of the type that could be used for pens, found inside the box of papyri. An ivory burnisher was also found nearby, which may have been used to prime the surface of papyrus sheets in preparation for writing with black ink.

These materials indicate that the tomb owner was literate and may even have been a lector, a professional associated with the priesthood who would read texts aloud during rituals.

Perhaps the most striking object of the group is a wooden figure of a naked woman with the face of a lion. This may have been intended to represent the mischievous god Bes or a deity named, Aha, meaning the fighter.

The statuette may also depict a human performer wearing a mask. An example of such a Bes mask, with evidence of wear, is known from the contemporary pyramid-builders town of Kahun.

Our wooden figure holds metal rods coiled in the shape of snakes, an attribute of Bes or Aha in iconography. The purpose of the female figure is unclear.

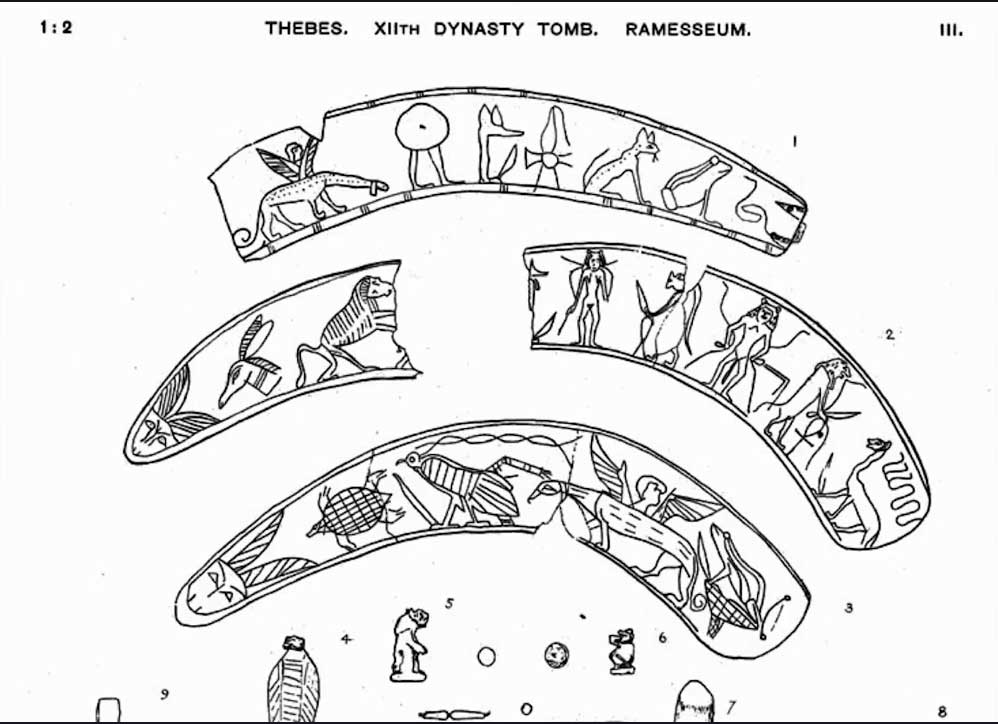

The Ramesseum tomb group also contained a number of carved hippo ivory tusks. These carry images of gods and animals, which provided protection, especially during the dangerous process of childbirth.

The ancient Egyptians observed that as well as being dangerous to humans hippopotami were also very protective mothers, making hippo-imagery well-suited to magically defending women and children from unseen forces.

Nude female figures in the group made from faience, a glazed material, were closely associated with promoting fertility.

Along with a pair of ivory clappers in the shape of human hands. This group of objects has led scholars to believe that the tomb group generally belonged to a practitioner of healing, a performer who may be likened to a magician.

We absolutely love your blog and find most of your post’s to

be just what I’m looking for. can you offer guest writers to write content available

for you? I wouldn’t mind publishing a post or elaborating on a few of the

subjects you write regarding here. Again, awesome blog!

Here is my web site … Inchirieri Auto