Apart from the all-important characteristic of population density, monsoon Asia—the area east of Afghanistan and south of what is now the Russian Federation—has other common features that make it an appropriate unit of study.

Even the monsoon part of Asia is a very large area, nearly twice the size of all of Europe to the Urals, and it is divided by mountains and seas into many sub-regions with different cultures, in many cases also inhabited by ethnically different people.

The four major subregions of monsoon Asia—India, China, Southeast Asia, and Northeast Asia (Korea and Japan)—are divided from each other in all of these ways and each is further subdivided, to varying degrees, into internal regions.

But there is a broad range of institutions, ideas, values, conditions, and solutions that have long been distinctively Asian, common to each of the four major parts of monsoon Asia, various at least in degree from those elsewhere, and evolving in Asia in peculiar ways.

These include, among many others, the basic importance of the extended family and kin network and its multiple roles; the respect for and importance attached to learning, for its own sake and as the path to worldly success; the veneration of age and its real or fancied wisdom and authority.

The traditional subjugation and submissive roles of women, at least in the public sphere (although Southeast Asia and southern India are qualified exceptions); the hierarchical structuring of society. The awareness of and importance attached to the past; the primacy of group welfare over separate interest; and much more distinctively Asian cultural traits general to all parts of monsoon Asia.

Agriculture |Culture of Asian

Except for Japan, and there only since the 1920s, most of Asia has traditionally been and remains primarily an agrarian-based economy. Although Japanese industry developed rapidly in the 1920s, and by 2012, China, India, and South Korea have become major industrial and commercial economies, Asian agriculture, including that of Japan today, has always been distinctive for its labor intensiveness, still in most areas primarily human labor, including that involved in the construction and maintenance of irrigation systems.

This too goes back to the origins of the large Asian civilizations, which arose on the basis of agricultural surpluses produced by labor-intensive, largely hand cultivation supported by irrigation. From the beginning, Asian per-acre crop yields have been upper than anywhere else in the world.

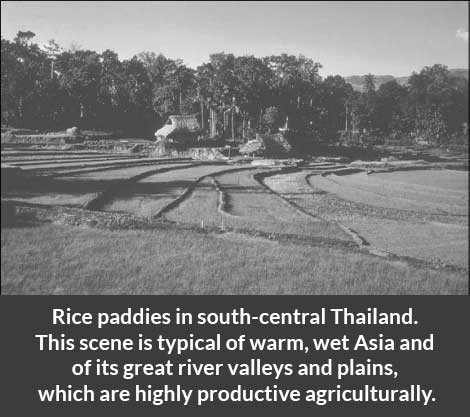

With the addition of manuring in later periods and chemical fertilization more at present, they are still the most in the world, especially in Japan. High yields have always supported large populations in monsoon Asia, concentrated in the plains, river valleys, and deltas, where level land and fertile alluvial (river silt) soils have also maximized output in this region of usually warm temperatures, long growing seasons, and usually adequate rainfall.

Since approximately the first millennium b.c.e. or even earlier, monsoon Asia has contained the largest and most productive agricultural areas in the world. As one consequence, population densities per square mile have also kept high throughout this time, especially on cultivated land, and upper than anywhere else until the present.

This was to some degree a chicken-and-egg situation. Productive land supported a growing population, which not only generate a need for more food but also provided the labor required to

Social Hierarchy

Very high population densities have had much to do with the equally consistent nature of Asian societies, especially their emphases on group effort and group welfare, their mistrust of individualism, and their reliance on a clearly stated and sanctioned system for behavior. Although the image of the hermit sage emerged early across Asia as a cultural alternative, individuals have almost always been subject to group direction and subordinate to group interest.

They were fitted into the larger structure of societies that were hierarchically organized; each individual has always had his or her defined place and prescribed role. Individual happiness and welfare, like those of the societies as a whole, have always been seen as resting on such a structure.

Most of these societies remain patriarchal and male dominant, although there are regional variations; the primary institution has always been the family, where the oldest member rules, sometimes a female but usually a male.

The chief virtue extolled by all Asian societies is respect and deference to one’s elders and to all others of higher status. Age and learning are equated with wisdom, an understandable idea in

It has constantly seemed strange to Asians that others elsewhere do not share to the same degree their own deference to age and to learning—and that they do not put the same high value on education as both the most useful and the most prestigious way for any individual to succeed in life.

But individual success is also seen as bringing both credit and material benefit to the family, and family obligation remains an unusually powerful drive for most Asians. From early on, it was possible for those born in humble circumstances to rise in the world by acquiring education, an effort that could be successful only with close family support and much family sacrifice.

Those who gain success, and all those in rebel or with education, were expected to set a good example for others. Indeed, society was seen as being held together by the model behavior of those at the top, from the emperor and his officials to the scholars, priests, and other leaders to the heads of families.

The family, the basic cement of all Asian societies, commonly involved three generations living together: parents, surviving grandparents, and children. But its network of loyalties and responsibility elaborate further to include to varying degrees cousins, uncles, aunts, mature siblings, and in-laws. It was a ready-made system of mutual support, often necessary in hard times but seen as a structure that benefited everyone at all times and was hence given the highest value.

There were of course strains within it, and within the societies as a whole, especially in the generally subordinate role of women, younger children, and others at the bottom. No society someplace has ever gained perfect solutions to all human problems, but these Asian societies seem to have been more successful than most, if only because they have lasted, in fundamentally similar form in these terms, far longer than any others elsewhere.

Except for in parts of Southeast Asia, a notable distinction, when women married they became members of their husband’s family and moved to his house and village. New brides were often subjected to tyranny from their

This patrilocal system was the norm in China, Japan, Korea, Vietnam, and India, or rather it became so as these civilizations matured. In prehistoric times and before the beginning of written records (quite late in Japan), it is likely that relations between the sexes were more egalitarian in these cultures. That seems to have been the case for the Indus civilization of India, before the Aryan migrations.

In early

Southeast Asia, including Vietnam even after its conquest by the Qin and Han dynasties, remained a world apart in terms of gender relations and is still so, with women more dominant and playing a major role in, for example, trade;

Individual privacy was largely absent, given the dense population, the family structure, and the pattern common to most of monsoon Asia whereby even in rural areas houses were grouped together in villages rather than scattered over the landscape on separate farms, as in much of the Western world.

Asian farms were little, averaging less than five acres in most areas, still lesser in the most deeply settled parts. Their exalted productivity as a result of intensive cultivation meant that a family could usually support itself on a relatively mini-plot or plots. These were grouped around each village, housing 20 to 50 families on average who walked the short distance to and from their fields morning and evening, all but the very young and the very old.

One was almost never out of sight or sound of others and learned early to adjust, to defer to elders and superiors, to work together in the common interest, and in general to accept living very closely with, virtually on top of, other people, realizing that clear and agreed-on rules for behavior were and are essential.

Marriage partners had to be sought in another village or town; most of one’s fellow villagers were likely to be relatives of some degree, and in any

The chief Asian crop, rice, is the most productive of all cereals under the care that Asian farmers gave it, irrigated in specially constructed paddies, or wet fields that are weeded,

Rice has demanding requirements, particularly for water, but where it can be raised it can support and must employ, massive numbers of people. In the drier areas such as north India and north China, wheat largely replaced rice as the dominant cereal, but it too could produce good yields under intensive cultivation.

More marginal areas could grow millet, sorghum, or barley; and in the southeast, taro, manioc, sago, and bananas supplemented grains. There was a short place for animals, besides for draft purposes including plowing and transport, although pigs, chickens, and ducks were raised as scavengers.

Cereals produced far more food per acre than could be obtained by grazing animals or feeding them on crops, and there was continual pressure to have the land yield as much food as possible to boost the dense populations.

Monsoon Asia has accordingly been called “the vegetable civilization,” centered on cereals and other plants (including a variety of vegetables) and minimizing meat in the diet, except for fish in coastal areas. Buildings were built primarily in wood, thatch, straw, and mud, with metal used only for tools and weapons, and stone hugely reserved for monumental religious or official structures.