Welcome to mylibrary24. In this post, we will explore aspects of the Old Kingdom of Egypt, concentrating on funerary architecture.

The old Kingdom of Egypt saw a series of powerful, quasi-divine kings, or pharaohs, ruling from the northern city of Memphis. Unfortunately, almost all the Old Kingdom domestic architecture (houses, palaces, and warehouses) was built from mud-brick and has been lost. The Old Kingdom temples, too, were built from temporary materials and have today vanished. In stark contrast, much of the stone-built funerary architecture remains.

Most of the Old Kingdom pharaohs built extensive stone pyramid complexes in Egypt’s northern deserts. Around these royal pyramids, Egypt’s elite built splendid stone tombs (known today as mastaba tombs). Their tombs, which were decorated with scenes and inscribed with hieroglyphic texts, allow us to understand something of the after-death expectations of Egypt’s elite.

Old Kingdom Pyramids

We will look at some of Egypt’s Old Kingdom pyramids. The diagram shown here is all taken from the book, The Real Story Behind Egypt’s Most Ancient Monuments (By Dr. Joyce Tyldesley). Almost all the kings of the older Middle Kingdoms built pyramid tombs in the desert cemeteries near their capital cities.

Their pyramids did not stand alone they were the most visible part of a larger funerary complex, which in most cases included a valley temple, a lengthy causeway, and a mortuary temple next to the pyramid. Queen consorts were buried in smaller pyramids within their husband’s complex.

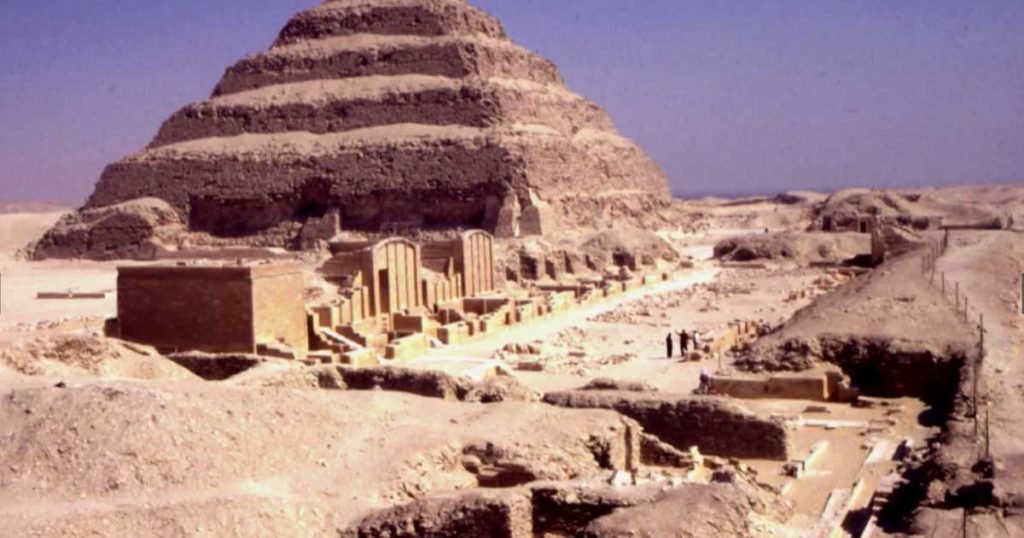

The first pyramid was built for King Djoser at the start of the Third Dynasty. This was not only Egypt’s first pyramid, but it was also Egypt’s first stone building.

Unfortunately, the bright white casing stone has been removed in antiquity. Djoser built his mortuary complex on the high ground at the Saqqara cemetery in Northern Egypt. This was a sensible location. Saqqara was well supplied with limestone quarries.

The inner pyramid was built from the rough cut, coarse, grained, local limestone. High-quality limestone was used for the visible casing. The burial chamber was lined with granite quarried at Aswan.

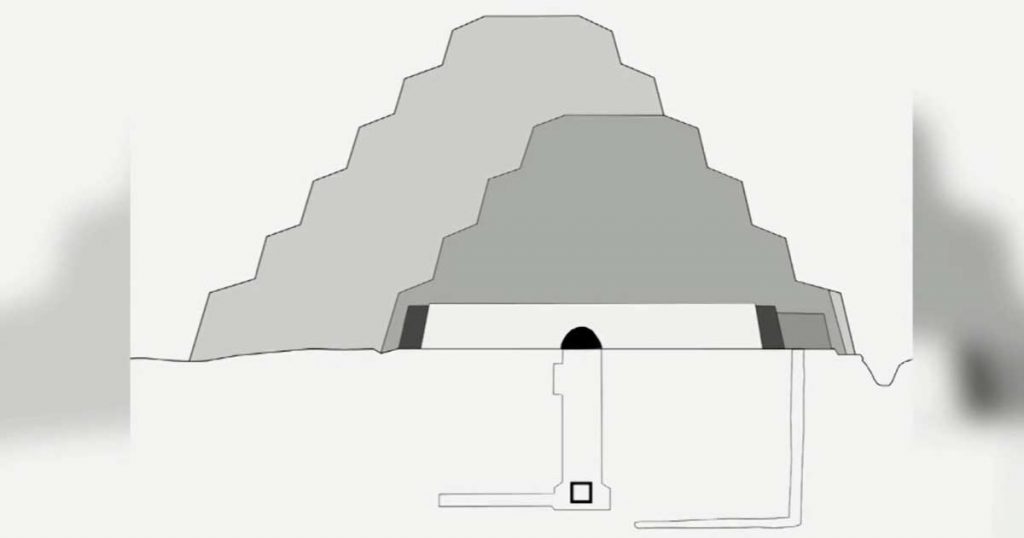

As you can see in the picture, this cross-section, Djoser’s pyramid was built in stages until it became an impressive six-step pyramid. His granite-lined burial chamber lies below ground. At the base of the wide shaft, it can only be accessed via a hole in the ceiling.

The burial chamber lies at the center of a maze of corridors and storerooms, some of which are part of the original plan and some of which have been made by ancient tomb robbers.

The pyramid was robbed in antiquity and Djoser’s body has never been found. It is, therefore, lucky that he had a substitute body. The serdab is a small, dark, and closed kiosk, resting against the side of the pyramid.

Here sits an almost life-sized painted stone pharaoh. Dressed in a long robe, cloak, and striped headcloth, the pharaoh stares through two eye holes gazing up at the northern sky, his eyes, once inlaid with precious rock crystal, have been mutilated and are now blank. It should be noted that this statue, currently in the serdab the statue that you can see here, is a replica. The original is in Cairo Museum.

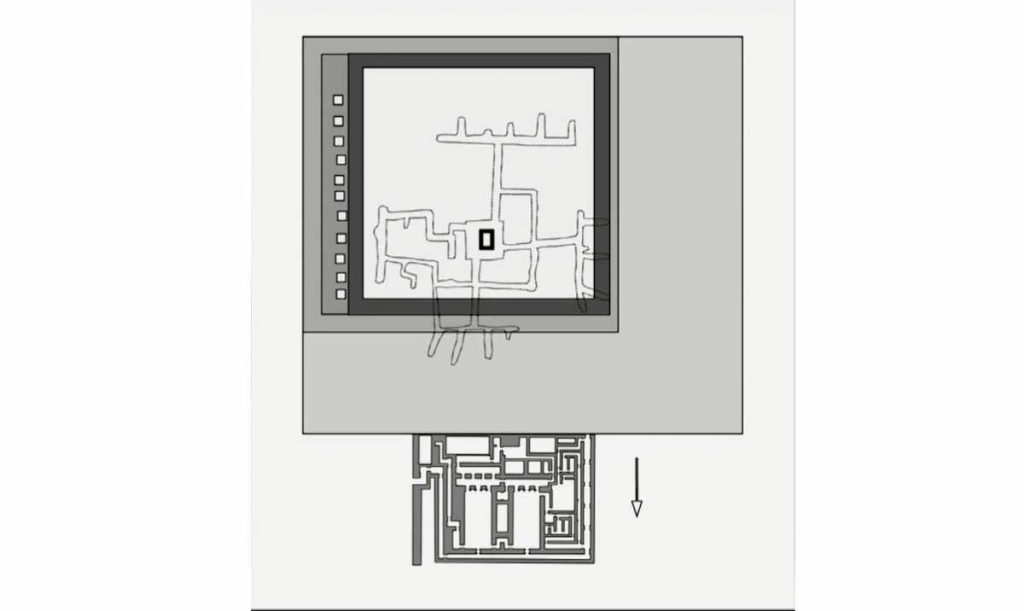

As you can see from this plan, the step pyramid was just one element in the Djoser mortuary complex. Inside a substantial wall, several buildings, the mortuary temple, in particular, were connected with the rituals of death and the cult of the dead King.

However, the Djoser complex also served as an eternal palace. To fulfill this role, it was provided with symbolic false buildings, stone replicas of Egypt’s most important shrines, plus permanent copies of the mud-brick and reed buildings used in the rituals of living kingship.

The kings of the Fourth Dynasty built true, or straight-sided, pyramids. The most famous of these is the so-called Great Pyramid, the pyramid built by King Khufu at Giza.

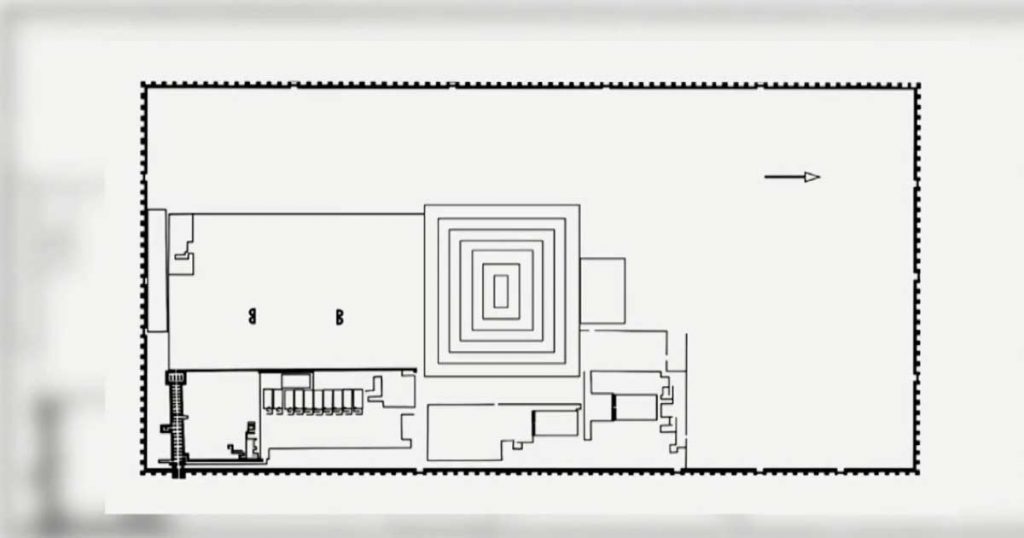

As this cross-section shows, Khufu’s pyramid holds three chambers linked by a simple system of passageways. From the entrance on the northern face, a steep passageway descends first through the body of the pyramid, then through the bedrock to level out, and then enter the subterranean chamber.

Partway along the descending passageway, still within the body of the pyramid, is the entrance to the equally steep ascending passageway. This opens into the grand gallery. A tall corridor whose walls are made from layers of overlapping limestone blocks. The lower west wall of the gallery includes a small hole that leads to the well.

A vent that drops almost to the end of the descending passageway. Here, too, is the entrance to the horizontal passageway which leads into the incorrectly named queen’s chamber. The grand gallery leads upwards to an antechamber, which gives access to the red granite burial chamber.

Here lay Khufu´s enormous red granite sarcophagus. The ceiling of the burial chamber is formed from nine massive granite slabs which started to crack as the chamber was being built. To prevent further damage, five stress-relieving chambers were provided directly above the burial chamber.

These spread the load of the pyramid. It is here, hidden from view, that we find the only pyramid inscriptions, casual scribbles left by the work gangs, which confirm that the pyramid belonged to Khufu.

Pyramids are nowhere explained. But many Egyptologists believe that they may have served as gigantic ramps or fossilized rays of sunlight, that would allow the soul of the dead king to travel upwards into the sky.

Seen from afar, pyramids look like islands rising out of the desert. The idea of mounds rising from water would have been very familiar to people accustomed to the annual Nile inundation. This idea is reflected in the Egyptian creation myth involving the god Atum.

At the beginning of time, nothing existed, except the still, dark waters of chaos. At the bottom of the waters lay an egg. Then suddenly the egg cracked open and life erupted. A mound rose out of the swirling waters. On this mound was a sun god Atum, he had created himself and had created light.

Atum went on to generate life on his island. First the gods than humans. This belief was translated into an association of mounds and islands with life and rebirth. Mounds were heaped over graves, and eventually, inside the dynastic temples, the ground would rise upwards towards the sanctuary.

The monumental buildings brought economic benefits. Old Kingdom Egypt experienced a steep learning curve as its builders were asked to produce stone columns, colonnades, porticos, and life-sized statues. An increase in bureaucratic efficiency was sparked by the need to coordinate the work of thousands of people.

Artisans, benefiting from unprecedented training opportunities, made huge leaps in technological ability. The constant demand for goods and access to top-quality materials allowed artists and craftsmen to perfect their skills. Less easy to assess, are the intangible benefits, the sense of national pride, and religious satisfaction which the completion of a pyramid might bring.

The Purpose of the Old Kingdom Tomb |The Old Kingdom of Egypt

I will be considering the purpose of the Old Kingdom tomb. What did the ancient Egyptians believe happened after death?

Our first evidence for the Egyptian view of life beyond death comes from the pyramid texts. A series of spells and incantations, first preserved in the 5th Dynasty pyramid of Unas. You can see the interior of his pyramid here.

These writings should be approached with caution. They’re highly complex and reflect earlier oral traditions, which are now lost to us. Egyptian theology was at all times a complex and constantly shifting matter. Changes in religious belief are not necessarily reflected in the archeological record.

Funerary traditions, in particular, tend to cling to familiar rituals, even when they have become essentially meaningless. It is clear that the Old Kingdom Egyptians believed that, given the right circumstances, the soul could survive death.

But not everyone could look forward to an afterlife free of the grave. Only the king could hope to escape. He would shine as an undying star in the night sky. Or he would accompany the solar god Re as he sailed his sun boat across the sky. Or he would become one with the god of the dead, Osiris.

His people might live again after death, but they were trapped forever within the tomb. Only at the end of the Old Kingdom, was it recognized that everyone had a soul strong enough to escape the tomb. Here you can see a typical Old Kingdom mastaba tomb.

The Egyptians believed that they had three distinct spirits or souls. All three, the Ba, the Ka, and the Akh would be liberated from the body at death. As long as these spirits flourished, they would enable the deceased to live on.

The Ba, shown here, represents the personality or individuality of the deceased. It was often depicted as a human-headed bird. The Ba was a strong and intrepid spirit, which lodged in the tomb, but which was free to come and go as it pleased. It could fly around Egypt, or it could leave earthly life behind, soaring to live with the gods.

The Ka or spirit of life was created as a parallel to the earthly body at the moment of conception. But the Ka was weak. Compelled to remain close to the corpse, it could never leave the grave and could not survive without nourishment. The dead were dependent on the living who would bring food and drink to the tomb.

Here we can see an offering being made. The Ka had one more requirement. For the Ka to survive death, the body had to survive in a recognizably human form.

The Akh was an ill-defined, even more, nebulas spirit representing the immortality of the deceased. With escape impossible, it became of paramount importance that the Old Kingdom non-royal tomb be made as large and as comfortable as possible.

No one wanted to dwell forever in a sand-filled pit. Everyone, even kings, filled their tombs with the food, drink, and luxury items that would sustain the Ka for eternity.

Funerary architecture would always have to vary with local geographical constraints. To take an extreme example, it would never be possible to build a large-scale pyramid in the steep-sided Valley of the Kings, as pyramids require a wide, flat base.

Local traditions, too, would play a part in tomb design. However, throughout Egypt and throughout the dynastic age, it would always be accepted that the tomb must serve a double function. It must protect the corpse and its belongings. And it must provide a focus for the offerings of food and drink which the family friends and employees of the deceased will leave to nourish the Ka.

We should, perhaps, add a third unwritten function. The two must adequately represent the status of its owner. Ownership of a large tomb in an elite cemetery was an obvious sign of social success.

Egypt’s elite faced some serious practical concerns. Frightened by the need to provide for all eternity, they attempt to take more and more goods to the grave. Clothing, cosmetics, jewelry, furniture, games, weapons, musical instruments.

Even in some cases a toilet. All were packed into the tomb so that the provincial cemeteries boasted unprecedented numbers of rich burials. And of course, unprecedented numbers of robberies.

The elite would continue to be buried with vast quantities of grave goods until at the beginning of the 3rd Dynasty, it was realized that the system was impossible. An eternity in the grave required infinite supplies of food and drink. Nothing less would suffice.

Magic offered an attractive alternative. The inclusion of a wall or stela carved with images of desired goods could substitute for the goods themselves. Within the tomb, these images would become both real and permanent. They could be supplemented by tomb inscriptions in the form of offering formulae or requests for material goods which will benefit the dead.

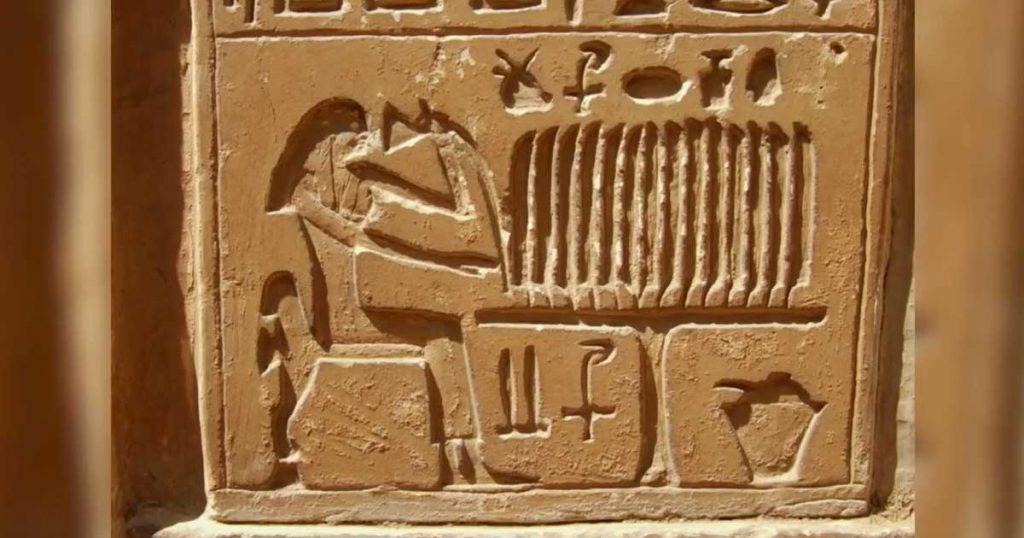

Here we can see a deceased person sitting in front of a table loaded with food. Supplied with an appropriately decorated tomb, an Old Kingdom member of the elite could be reasonably sure of a comfortable afterlife. The expectations of the poor, who continued to be buried in desert pit graves, are less easy for us to assess.

Ankhtifi |The Old Kingdom of Egypt

In this section, I’ll introduce you to an individual named Ankhtifi. Ankhtifi was a warlord who lived in the First Intermediate Period. That’s around 2,100 BCE.

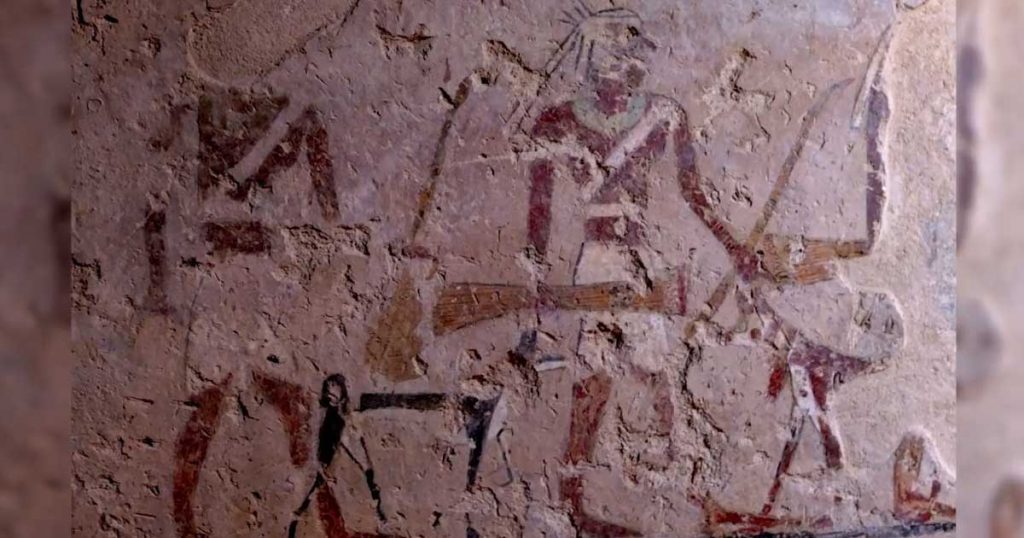

Here you can see Ankhtifi standing in his tomb. His broad collar, staff, and scepter identify him as a high-ranking individual. This was a time during which there was no single king of Egypt. Instead, the country was fragmented with different local rulers attempting to claim the throne.

We know about Ankhtifi thanks to his large and well-decorated tomb. His tomb particularly his long hieroglyphic inscription is one of the main sources of information for the events that took place during the First Intermediate Period.

Here you can see the interior of the Tomb of Ankhtifi. At some point in the past, the roof collapsed damaging the interior of the tomb. It was cleared and a modern roof put in place early in the 20th century.

Although the tomb has clearly suffered damage much of the rich decoration and hieroglyphic texts still remain for us. Ankhtifi lived and died at a place called Hefat. Which is an ancient Egyptian town. It’s 50 kilometers or 30 miles south of modern Luxor. We’re not sure exactly where Hefat was, but presumably, it lay fairly near to Ankhtifi’s tomb.

This image looks out from the tomb towards the River Nile and beyond. Ankhtifi tells us that he rules over a large area in southern Egypt from just south of Luxor down to Egypt’s southern border Elephantine near modern Aswan.

He also tells us that his nearest neighbors are his biggest enemies, the Thebans. Ankhtifi’s inscriptions describe his battles with the Thebans, with each side attempting to dislodge the other and reunify the land under a single king.

He tells us, for example, and you can read this in the translation shown on the image,

I moved north and moored on the east of Thebes. Its walls were besieged. It had bolted its gates through fear. This faithful body of troops of mine became seekers throughout the west and the east of Thebes, but no-one dared to come out through fear.

Ankhtifi

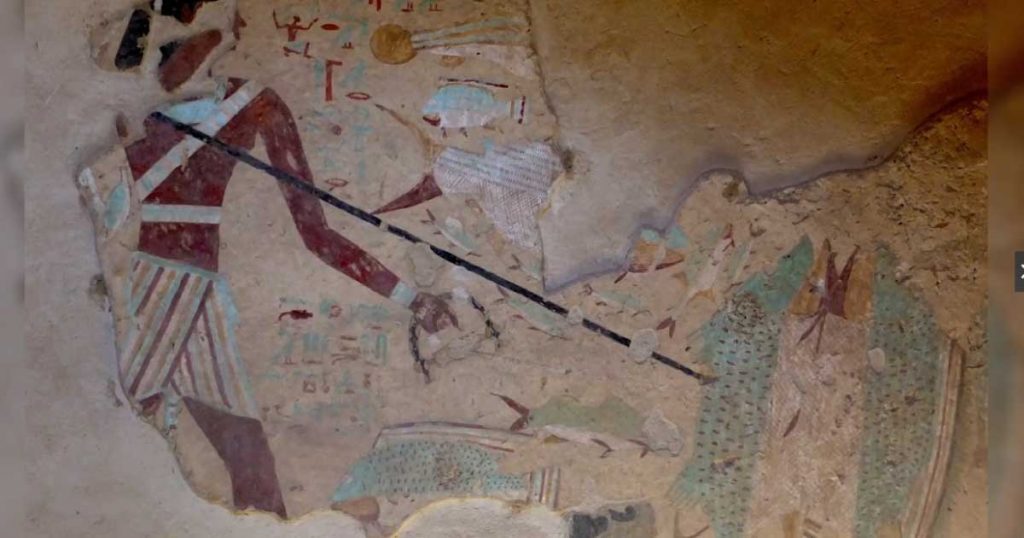

Ankhtifi refers to his trusted troops fairly frequently. These troops are also depicted in his tomb, carrying bows and arrows with their hunting dogs. Interestingly, archaeological evidence further bolsters the picture. The Supreme Council of Antiquities in Egypt, along with the University of Liverpool, UK have been working at the tomb. And have discovered a fragment of the bow in the forecourt of Ankhtifi’s tomb.

This was most likely left there as a result of tomb robbery in ancient times. Note how it matches the style of the bow painted inside the tomb rather well. The longbows made from a single piece of wood appear to be the self bow type. And the fact that the warriors are holding arrows agrees with what we know about quivers not being used until a little later In the Middle Kingdom.

Now unfortunately for Ankhtifi, he doesn’t manage to ultimately defeat the Thebans and reunify the country. We know this because eventually, we see strong evidence from the Thebans to show that one of their rulers, Nebhepetre Mentuhotep II finally defeated his enemies to become the first king of the Middle Kingdom.

It’s from this point in Egyptian history that Thebes becomes a really important and prominent city, as it remained for the duration of pharaonic history. This is clearly seen in the way in which it was embellished by kings over the centuries, resulting in the complex temples and busy cemeteries that can still be seen today.

It’s interesting to consider how different Egypt might have looked if someone like Ankhtifi had reunified the land. As well as the battles with the Thebans, Ankhtifi tells us how important he was for his local community. A clear example of this is his famine inscription. He says,

all of Upper Egypt was dying of hunger, with people eating their own children. But I never let anyone die of hunger in this nome.

Rather than seeing this as evidence for a devastating drought that led to cannibalism, scholars consider that Ankhtifi is taking the common issue of food shortage and exaggerating it somewhat in order to demonstrate how efficient he was as a leader. Never letting his townspeople go without food, no matter how things were elsewhere.

This highlights an interesting point. These tomb inscriptions are not straightforward histories. The ancient Egyptians were not recording events for us historians to learn about. They were recording events for the specific purpose of demonstrating how valuable they were to their communities and their gods.

It was the ancient Egyptian belief that if they’d lived a good and just life, they would be worthy to receive an afterlife, where they would continue to live for eternity. Ankhtifi takes this purpose quite far, and we might consider some of what he says to be quite boastful. For example, he says,

I am the beginning of men and the end of men. For my like shall not be, nor could he ever be; my like has not been born, nor could he ever have been born.

Here is an image of Ankhtifi fishing from his tomb. Although the scene itself is quite damaged, note the fantastic use of color and imagine how splendid this tomb would have been in its heyday.